GI Radiology > Esophagus > Esophagitis

Esophagitis

![]()

Infectious Esophagitis |

|

Clinical Infectious agents that can cause esophagitis include: Candida, herpes, cytomegalovirus, or tuberculosis. These infections are often opportunistic infections and have been on the rise because of the increased survival of immunocomprised patients. Candida esophgitis: Candida is the most common cause of infectious esophagitis. C. albicans is the most common organism, but it can also be attributed to C. tropicalis, C. pseduotropicalis, and c. kruzei. C. albicans is part of the normal flora of the pharynx and can therefore infect the esophagus in immunocompromised patients, particularly AIDS patients. Clinically, patients may present with acute onset of odynophagia, with substernal pain and burning with swallowing. Patients may also develop dysphagia secondary to the formation of esophageal strictures. Radiographically, Candida esophagitis is difficult to detect on single contrast studies with an overall sensitivity of less than 50%. Double contrast esophagography however has a sensitivity of approximately 90%. On double contrast studies, Candida esophagitis manifests as discrete plaque-like lesions that tend to be longitudinally oriented. They appear as irregular filling defects with normal intervening esophageal mucosa. The borders are very discrete and etched between a thin layer of barium. The esophagus can also have a fine nodular or granular appearance secondary to mucosal edema and inflammation. In severe cases, the esophagus appears grossly irregular with a "shaggy" contour due to plaque and pseduomembrane formation.

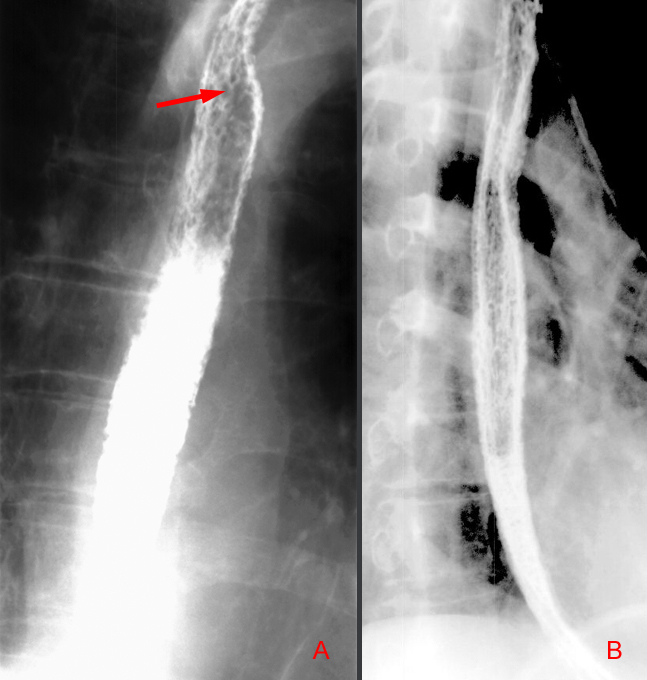

Canida - Above is a characteristic "shaggy esophagus" associated with Canida infection. Image "A" depicts the longitudinally oriented plaque-like lesions visible in Candida esophagitis. Image "B" depicts the granular appearance of the esophageal mucosa secondary to edema and inflammation.

Herpes esophagitis: Herpes simplex virus type 1 is the second most common cause of opportunistic esophagitis in immunocompromised patients, but can not be excluded in a patient with a normal immunologic status. Patients typically present with acute odynophagia with severe substernal chest pain during swallowing. Dysphagia, chest pain, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding are less often observed. The presence of herpetic lesions in the oropharynx should also suggest the possibility of herpes esophagitis. In immunocompetent patients, patients may complain of a 3 to 10 day influenza-like prodrome consisting of fevers, myalgias, sore throat, or upper respiratory symptoms. Radiologically, herpes esophagitis will present typically as discrete, superficial ulcers in the midesophagus. The ulcers can have a punctuate, linear, ring-like, or stellate configuration and are often surrounded radiolucent halos of edematous mucosa. In contrast to Candida esophagitis, these ulcerations are visible without evidence of plaques. However, advanced herpes esophagitis may be associated with extensive ulceration and plaques and therefore be indistinguishable from Candida esophagitis.

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis: CMV is a member of the herpes virus family and is a less common cause of esophagitis in patients with AIDS, and is even more rare in other immunocompromised patients. CMV esophagitis usually presents with sever odynophagia. Radiologically, CMV esophagitis manifests as discrete, superficial ulcers that are almost indistinguishable from herpes esophagitis. Some may also have localized ulcerations, nodularity or thickened esophageal folds. Again, the ulcers may be surrounded by a radiolucent rim of edematous mucosa.

Tuberculosis esophagitis: Tuberculosis of the esophagus is extremely uncommon and is usually secondary to terminal disease in the lungs. Esophageal involvement may result from swallowing infected sputum, direct extension from laryngeal or pharyngeal lesions, from adjacent tuberculous nodes in the mediastinum that compress or erode into the esophagus, or rarely from hematogenous seeding in patients with disseminated miliary tuberculosis. Patients may present with odynophagia, chest pain, or dysphagia. Radiologically, contrast

studies will show ulcers, plaques, fistulas, and mucosal irregularity.

It may be difficult to distinguish tuberculosis esophagitis from severe

esophagitis secondary to ingestion of corrosive agents or radiation exposure.

If there is extrinsic involvement of tuberculous nodes, the esophagus

may be compressed, displaced or narrowed by the adjacent mass. Strictures

or traction diverticula tend to develop in these cases. If these caseating

nodes erode into the esophagus, they may produce areas of ulceration,

sinus tracks, or fistulas into the mediastinum or trachea. |