|

Untreated thoracic

esophageal perforations have a near 100% mortality rate because of the

fulminant mediastinitis that occurs afterwards. Perforation of the cervical

esophagus is more common and has a lower mortality rate, 15%. In either

case, early detection is important in order for prompt surgical intervention.

Perforation can be due to iatrogenic causes (i.e. endoscopic procedures,

pneumatic dilatation balloons, nasogastric tubes, endotracheal tubes),

foreign bodies, trauma, or spontaneously (Boerhaave's syndrome-see next

section).

Clinical

Cervical perforation often occurs as a complication of endoscopy. Patients

may present with dysphagia, neck pain, fever, or subcutaneous emphysema

in the neck. Cervical esophageal perforations heal with conservative treatment

with antibiotics, but larger perforations may require cervical mediastinotomy

with open drainage to prevent abscess formation.

Radiological findings

On plain films, subcutaneous emphysema may be visible on AP or lateral

films of the neck. Air may also dissect into the chest and produce a pneumomediastinum.

Lateral films of the neck may reveal widening of the prevertebral space,

anterior deviation of the trachea, or a retropharyngeal abscess with an

air-fluid level. If a cervical perforation is suspected on plain film,

the study should be followed up with a water-soluble contrast study.

Water-soluble contrasts are rapidly absorbed from the mediastinum, whereas

barium has been shown to excite an inflammatory response with fibrosis.

However water-soluble contrasts may miss 15 to 25% of perforations because

they are less radiopaque than barium. On the esophogram, one would look

for localized extravasation of contrast medium into the neck or mediastinum.

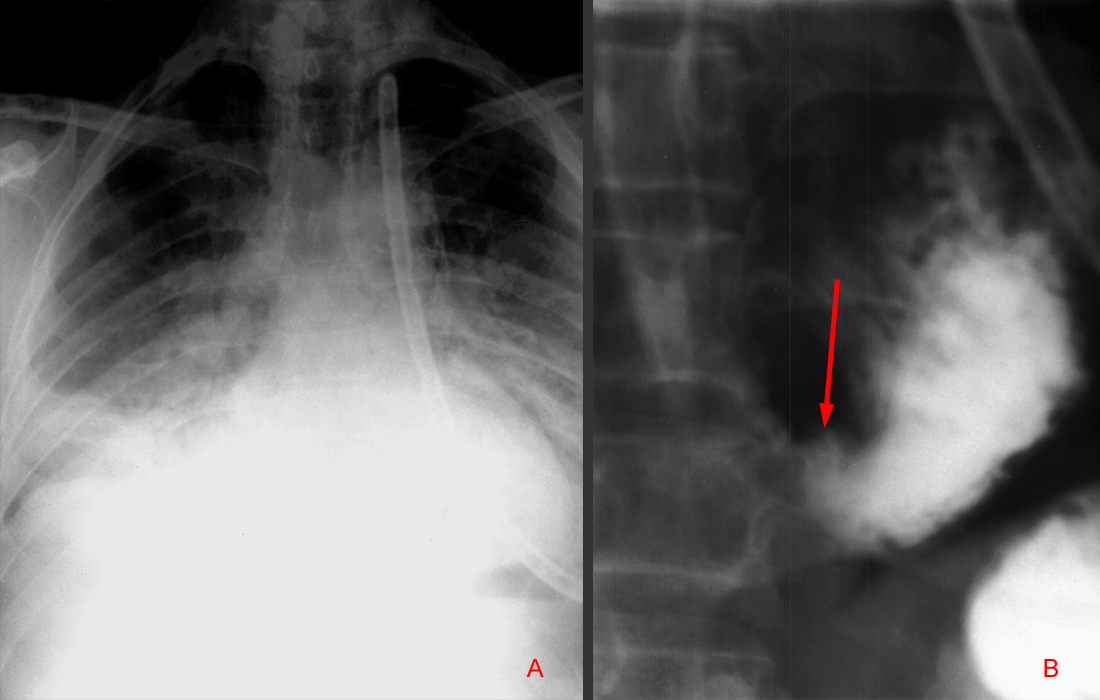

In

image "A", this frontal view of the chest shows evidence of

mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema with pneumonitis. Image "B"

reveals an esophagram with extravasation of contrast from the esophagus.

Clinical

Thoracic perforation often present with the classic triad of vomiting,

lower thoracic chest pain and subcutaneous emphysema. Refluxed stomach

acid or swallowed food/saliva may enter the mediastinum and cause severe

mediastinitis. If no subcutaneous emphysema is present, thoracic esophageal

perforations are often mistaken as perforated peptic ulcers, MI, spontaneous

pneumothorax, pancreatitis, dissecting aortic aneurysm, or mesenteric

infarction. After 24 hours, the mortality rate for thoracic perforation

approaches 70%. Unlike cervical perforations, thoracic perforations are

treated immediately with surgery and drainage.

Radiological findings

On plain films, a widened mediastinum and pneumomediastinum may be present.

Also, approximately 75% of thoracic esophageal perforations are associated

with a pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax. Left pleural effusions often

occur because of irritation of the adjacent parietal pleura and pulmonary

parenchyma. Hydropneumothorax can occur if the mediastinal pleura ruptures

and gas and fluid may enter the pleural space directly from the mediastinum.

On esophagram, contrast media is usually seen extravasating from the left

lateral aspect of the distal esophagus because most thoracic perforations

occur near the gastroesophageal junction.

|

![]()